Biography lends to death a new terror ~ Oscar WildeMelmoth, the sixth and shortest of the separate ‘graphic novels’ that make up the work Cerebus, is, at two hundred pages, described by its author/co-artist Dave Sim as a ‘short story’, because it takes so little time to read in comparison with his longer, more obviously dense works. Melmoth is a huge departure from everything that Sim had done before in Cerebus, not advancing the plot of the main series at all until the epilogue, but rather telling the story of the death of Oscar Wilde through the letters of the friends who were with him in his last days.

On the surface Wilde may seem a strange subject for Dave “the feminist/homosexualist/islamofascist/Marxist conspiracy are reading my mind when I masturbate” Sim, but Melmoth is the work of a very different Sim to the one we have today – a man who had recently contributed a story to Alan Moore’s GLAAD compilation (a benefit comic to attack anti-gay laws in the UK), and who dedicated this work to a cousin of his who had recently died of AIDS. And Sim treats the subject with the respect that it deserves.

After the emotional climax of Jaka’s Story (still, to my mind, the single greatest graphic novel ever created, by quite a long way) Sim had a year to kill before getting back to his gigantic political-religious conspiracy plot, and so he decided to keep the title character sidelined (Cerebus himself had not appeared for a year at the start of Melmoth, having gone off to buy a bucket of paint at a crucial moment and missed the climax of Jaka’s Story), having Cerebus appear for a handful of comic relief pages each issue, completely catatonic after the shock of Jaka’s Story‘s ending, while Sim told the real story – the story of the death of Wilde, drinking himself to death under an assumed name in exile.

After the emotional climax of Jaka’s Story (still, to my mind, the single greatest graphic novel ever created, by quite a long way) Sim had a year to kill before getting back to his gigantic political-religious conspiracy plot, and so he decided to keep the title character sidelined (Cerebus himself had not appeared for a year at the start of Melmoth, having gone off to buy a bucket of paint at a crucial moment and missed the climax of Jaka’s Story), having Cerebus appear for a handful of comic relief pages each issue, completely catatonic after the shock of Jaka’s Story‘s ending, while Sim told the real story – the story of the death of Wilde, drinking himself to death under an assumed name in exile.And it’s done beautifully. Other than some dialogue in the early pages, every detail of the story is taken directly from the letters of Wilde’s friends Robert Ross and Reginald Turner, both dialogue and caption narration, with the only changes being the replacement of real-world place names with their comic-world equivalents (and the letters are reproduced in full in the end notes). We see Wilde slowly dying, starting off with him clearly ill but able to walk and converse, and ending with him emaciated and incoherent. Along the way he’s clearly trying to pretend, to himself as much as his friends, that he’s OK, but he looks visibly more distraught in almost every panel, as the realisation of his imminent death hits him, while also so tired he clearly almost welcomes death.

With little in the way of real writing to do, the story has to be carried by Sim and Gerhard’s art, and luckily they were both at their peak here. Sim, in particular, while he’s not doing the formal experimentation of earlier or later stories, manages to use an art style that is distinctly his own but also very strongly hints at Wilde’s contemporaries (some panels look to me exactly like Beardsley, though he denied any influence when I asked him about it in a chat on the Cerebus mailing list).

But it’s the fact of Sim not writing – as such – this story (about a writer who’s no longer able to write), that points to its deeper ‘message’. As much as Melmoth is about Wilde, in the wider context of Cerebus it’s about the impossibility of writing a true biography.

While Sim has always used real people in his stories (Mrs Thatcher, Mick ‘n’ Keef, Groucho Marx), Wilde is the only person who has become three separate characters in Cerebus. The character of ‘Oscar’ (no surname) appears in Jaka’s Story and, it’s later revealed, is the narrator of the bulk of the story. At the time of Melmoth‘s publication it was left ambiguous as to whether that Oscar and the one here were one and the same, though they’re physically dissimilar (‘Oscar’ was a baloonish caricature, while the Wilde here is a far more naturalistic drawing) and Wilde (in one of the few bits of original dialogue here) praises “Daughter of Palnu” (the book-within-a-book written by Oscar in Jaka’s Story). That ambiguity was later cleared up by an appearance of ‘Oscar’ in a couple of panels, still alive, but at the time of writing Sim thought the ambiguity an entirely good thing.

A third Wilde, under the name Lord Henry Wooton (to whom many of Wilde’s anecdotes, and Sim’s own pseudo-Wildean epigrams, are attributed), appears several times as well in Cerebus, but Wooton is a creature of text – he’s never drawn, we never see him, he’s just written about and talked about, and we draw our impressions of him from what other people say he said.

And this is the real crucial point about Melmoth, because what it’s really about is only apparent in the context of the wider work of which it’s a part, although some clues are given in the foreword and appendices to the collection, where Sim says:

Each biographer selects those elements of Wilde’s life he finds pertinent and, not incidentally,which reinforce whatever thesis he brings to the story.and

It was only when I began drawing the last day, together, of Ross and Oscar Wilde that I became suspicious of his narrative…The fact that Reggie and the nurse had been asked to leave (I asked the nurse not to exist myself) meant that Ross was free to describe their good-bye in any way he saw fitSim was very deliberately fictionalising a narrative he already regarded as unreliable. But to understand why, you have to look at Jaka’s Story and Mothers And Daughters, the two longer graphic novels that come either side of this story. In Jaka’s Story, almost everything we think we’re being told in flashback turns out to be a novel written by ‘Oscar’, based on stories told him by Rick, who heard them from Jaka, who may be lying or misremembering herself – the supposedly-omniscient narrator is in fact giving us third- or fourth-hand fictionalised versions of the truth (except that there is no truth, of course, because it’s still a work of fiction). The one character who contradicts Oscar’s version, though, Jaka’s old nurse, is such an obviously-biased person that her word can’t be taken as truth, either.

Meanwhile in the next story, Mothers And Daughters, David Victor Sim introduces three new characters – two of whom are, like Henry Wooton, only known through text. The first is Viktor Reid, who is friends with Wooton and who lives through a very-vaguely fictionalised version of the early-’90s comic scene. The second is Victor Davis, who writes and draws a comic called Cerebus, and whose views on women made the majority of Sim’s readership disappear, and who makes public in the text of the comic the extra-marital affair of at least one prominent then-married comic writer, among other indiscretions. And finally there’s ‘Dave’, a voice from the void who, in the couple of panels at the end of the story where he’s seen, looks like Sim, and who can converse with Cerebus and has complete control over his world (the similarities to Morrison’s Animal Man climax are probably due more than anything to both having seen Duck Amuck).

So Sim is almost using Wilde as a ‘fiction suit’ – both as a foreshadowing of the big scene fifty issues later where ‘Dave’ and Cerebus finally talk, but also as a way of reifying the view Sim took until he got a religious component to his mental illness – that there is no single truth, but a plurality of part-truths, and all we can do is examine everything that’s presented to us and try to see things from as many angles as possible.

Wilde’s death is also, of course, the half-way mark of Cerebus, and Wilde’s death – estranged from his family and most of his friends, his reputation in tatters, incoherent and unable to write – is presumably meant to mirror Cerebus’ death at the end of the full 6000-page story, with Cerebus dying ‘alone, unmourned and unloved’. One can only hope that Sim’s own rejection of nearly all human contact won’t lead to the same fate for him, no matter how much he may appear to wish for it.

Because for all that Sim’s work at its peak argues there is no true truth, there still really was a man called Oscar Wilde, he really did die in a manner something like the drawings in this book, and as the book makes clear, it wasn’t romantic, it wasn’t poetic, it was a lonely man rotting away from the inside. And it’s a tribute to the book’s strength that for all its cleverness, its fictional setting, its deliberate lies and misreported facts, and its larger point, that truth still comes through and makes us care for a man who died more than a hundred years ago, represented by a few ink lines. ~ Source

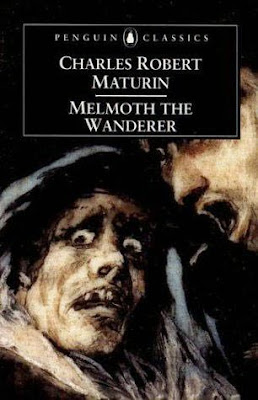

Stanton was thinking thus, when all power of thought was suspended, by seeing two persons bearing between them the body of a young, and apparently very lovely girl, who had been struck dead by the lightning. Stanton approached, and heard the voices of the bearers repeating, "There is none who will mourn for her!"The central character, Melmoth (a Wandering Jew type), is a scholar who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for 150 extra years of life and spends that time searching for someone who will take over the pact for him. The novel actually takes place in the present, but this back story is revealed through several nested stories-within-a-story that work backwards through time (usually through the Gothic trope of old books).

Saint Sebastian was a Christian saint and martyr, who is said to have been killed during the Roman emperor Diocletian's persecution of Christians. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post and shot with arrows.

Saint Sebastian was a Christian saint and martyr, who is said to have been killed during the Roman emperor Diocletian's persecution of Christians. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post and shot with arrows.More information is available at Saints & Angels - Catholic Online and Wiki

No comments:

Post a Comment